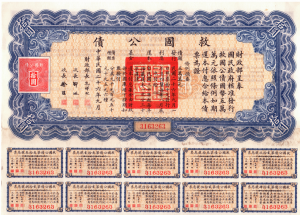

1937 Liberty Bond – National Government of the Republic of China

Costituzione: 1937

Codice ISMIN: 30517

La Repubblica di Cina è stata fondata nel 1912 e ha governato la Cina fino al 1949, quando ha perso il continente durante la guerra civile cinese e si ritirò a Taiwan. Nel 1937 nel 26 ° anno della fondazione della Repubblica, “Liberty Bonds” sono stati emessi in tagli da $ 5, $ 10, $ 50, $ 100, $ 1.000, e 10.000 $.

Il titolo con la denominazione $ 10.000 è assai raro e attualmente non viene segnalato nel mercato da storico da parecchi anni. Molti sono apparsi ma sono delle copie non originali.

Il set di 5 denominazioni di $ 5, $ 10, $ 50, $ 100, e il raro 1.000 dollari è indicato come una “Escalera”, o “suite”. La domanda per questo set è incredibile ed il prezzo per questi titoli storici è in continua ascesa. Il taglio più’ raro da 1.000$ ha r... Altro

La Repubblica di Cina è stata fondata nel 1912 e ha governato la Cina fino al 1949, quando ha perso il continente durante la guerra civile cinese e si ritirò a Taiwan. Nel 1937 nel 26 ° anno della fondazione della Repubblica, “Liberty Bonds” sono stati emessi in tagli da $ 5, $ 10, $ 50, $ 100, $ 1.000, e 10.000 $.

Il titolo con la denominazione $ 10.000 è assai raro e attualmente non viene segnalato nel mercato da storico da parecchi anni. Molti sono apparsi ma sono delle copie non originali.

Il set di 5 denominazioni di $ 5, $ 10, $ 50, $ 100, e il raro 1.000 dollari è indicato come una “Escalera”, o “suite”. La domanda per questo set è incredibile ed il prezzo per questi titoli storici è in continua ascesa. Il taglio più’ raro da 1.000$ ha raggiunto in alcuni casi prezzi intorno ai 50.000 $.

Sembra che l’alta richiesta per questi titoli cinesi sia da attribuire da una serie di dispute legali per capire se in qualche modo possono essere ancora validi ed essere incassati.

Ecco alcuni testi che abbiamo trovato on line in lingua originale:

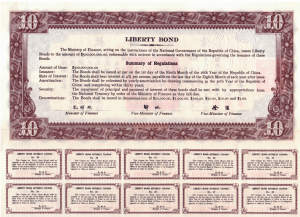

Our Dad was unwaveringly patriotic to Canada but he never lost his quiet but undying sense of loyalty to his homeland in China. And it was because of being Chinese that he bought some Republic of China Liberty Bonds in between World Wars as his small contribution to help with the re-building efforts. In fact, he kept these bonds in his files and never considered redeeming any of the coupons when the interest came due so his small contribution would remain in China. I was looking at this $10.00 certificate recently, printed in Chinese on the front with a decent English version on the back (click on the smaller images to enlarge in a new window for easier viewing).

NOTE: The 26th Year of the Republic of China referenced on the bond was 1937 and the 59th Year of the Republic when the final interest coupon came due was 1970! So these bonds were supposed to be paid out over 33 years until maturity! And which were apparently never actually re-paid from what I only recently discovered (see the article at the end of this post).

While I was looking the bond over, I happened to come across a very interesting article about these bonds, along with some new revelations about what happened to Chinese debt after the Great Revolution and a lot of other questions:

China’s secret? It owes Americans nearly $1 trillion

By RICHARD PARKER

China has a secret: It owes American investors hundreds of billions of dollars.

The Chinese government doesn’t like to talk about it and the U.S. government doesn’t want to raise it. But decades ago, Beijing defaulted on debt owed to Americans, as well as investors and governments around the world. In one case, it was paid. In the rest it was not. More than 20,000 American investors own this debt. The U.S. government may also own Chinese war debt, unpaid since World War II.

With the simple stroke of an executive proclamation, President Barack Obama can begin the process of addressing this issue. A 1930s-era law has established a quasi-public agency within the Securities and Exchange Commission, known as the Corporation of Foreign Securities Holders, which can arbitrate this dispute, much as a predecessor agency did for decades. China can both afford and benefit from this solution; it will afford goodwill at a time when relations between the world’s two superpowers are strained.

The story begins nearly 100 years ago, in 1913, when the government of China began issuing bonds to foreign investors and governments for infrastructure work to modernize the country. As the country fell into civil war in 1927, paying these debts became increasingly difficult and the government fell into default. Even so, in April 1938, the Nationalist government of China began to issue U.S.-dollar denominated bonds to finance the war against Japan’s brutal invasion.

Locked in a pitched battle for survival, the government issued these bonds into 1940. As part of its wartime financial aid, the U.S. government further provided a $500 million credit to China in March 1942, shipping gold there and helping to stabilize the currency. In return, it appears that the U.S. government redeemed some of these dollar-denominated bonds. But China doesn’t appear to have

repaid this debt either, according to State Department records, and the declaration of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 ended decades of political, military and financial cooperation.

While successor governments are usually bound by the debts of predecessor governments, the new Communist government refused to pay any of these claims. The issue lay dormant for decades, just as the bilateral relationship did. Then, in 1979, as part of normalizing relations, Washington released government financial claims regarding the expropriation of American property and appears to have dropped the matter of the war debt entirely.

However, individual citizens remain with claims to press. Some U.S. investors tried to sue the Chinese government in the 1980s and 1990s. However, the Foreign Sovereign Immunities Act makes it very hard for any U.S. citizen to sue a foreign government in U.S. courts because the law generally says that U.S. courts do not have jurisdiction.

Today, the Chinese bonds held by U.S. investors may be worth as much as $750 billion.

In general, governments do inherit the debt of their predecessors just as they inherit the assets of the nation. Governments have defaulted on debts since at least the 4th century B.C., when 10 of 13 Greek cities could not pay their bills; ironic, yes. And there is a long history of settlements, too. In the last 200 years, more than 70 governments, from Austria to Vietnam, have defaulted and eventually settled for far lesser amounts, allowing them to borrow once more.

Examples abound. An international arbitration panel found that post-revolutionary Iran needed to pay the United States for military aid in 1948. Post-apartheid South Africa has not repudiated debt incurred under the previous regime. In 2006, Great Britain paid the final installment on a World War II-era loan from the United States and Canada, and even sent a thank-you note. Russia has paid debt incurred under the tzars. One exception argued by governments is that in some cases a previous regime’s debt is “odious.” That is, the debt was incurred to enrich the regime or oppress the people.

Neither seems the case in China, which may be why it has never submitted to international adjudication. China, for its part, has not exactly disavowed the debt; it simply has selectively refused to pay it.

Technically, this calls into question China’s stellar credit ratings and those of its government-owned enterprises. But specifically, the U.S. government has a legal obligation to its citizens. The 1933 Securities Act established both the Foreign Bondholders Protective Council, under State and Treasury, and the Corporation of Foreign Security Holders, under the SEC, to get foreign governments to address debts owed to private U.S. investors. Housed in a Virginia suburb, the council in 47 instances settled the debts of foreign governments, including communist ones, to U.S. citizens. In 1975, the Polish government paid U.S. investors one-third the face value, or $8.5 million, of nine different series of bonds, all inherited from previous governments.

Indeed, President George W. Bush’s counsel directed the bondholders to the council in 2001 but the council did nothing, most likely to keep from rocking the bilateral U.S.-China boat. Now, the council is shuttering its doors, as it has completed dozens of cases and no administration wanted to refer the Chinese case for fear of upsetting Beijing again. However, the Corporation of Foreign Security Holders is still on the books and represents the only chance for U.S. investors to be paid.

All that has to happen is that Obama issue a proclamation to stand up the corporation, and a staff, at the SEC. The bondholders would bring their bonds in for examination and verification of the certificates and serial numbers. Then the corporation could get about settling the issue through payment, reissue of bonds, restructuring or even settling the debt. The reality is that a settlement could benefit everyone. Yes, it will be politically distasteful in Beijing. But in all likelihood, a settlement would likely be struck for a fraction of the face value of the bonds. Unlike 1949, China today has the ability to pay. It would be seen as good faith by Americans. And that, in turn, would help reassure us about China’s increasingly important place in the world. There are simply too many other questions about about China’s peculiar brand of state capitalism.